Anastasia Campbell (Heritage and Memory Studies, University of Amsterdam)

In April 2020, a unique archeological finding was made on the grounds of the police academy in Leusden, which was once the territory of a Second World War transition-prison Kamp Amersfoort (1941-1945). This was a metal cigarette box with a name, date and drawing carved on it with the Cyrillic letters spelling a name on it. Making it a quintessential discovery concerning the 100 Soviet soldiers imprisoned at Kamp Amersfoort during the Second World War. This finding sparked the start of a new research project, aimed to find out more about the phenomenon of Soviet trench art in the Netherlands during the Second World War.1

To find out if there may be more similar pieces of art scattered across the country, together with the researcher and collection manager at the National Monument Kamp Amersfoort, we reached out to a wide number of World War Two monuments, organizations and archives across the Netherlands. Through this process, we got a number of responses leading us to the discovery of six more pieces of Soviet Trench Art in the Netherlands.

What is the function of this inventory?

In this inventory you will find photos and details of the origin, dimensions and materials of each of the seven pieces of trench art. These details will be followed by my some of my thoughts and interpretations of the art, as based on what we know to be true about the pieces and some extra research. My primary goal here is to attempt to make some sense, and draw lessons where possible from these pieces of trench art. In some cases, this section of ‘Description and reflections’ will be bigger, and at times much smaller. This will be because it is important for me not to force interpretations upon these objects, as to avoid fixing unverifiable ‘facts’ and narratives. I will only speculate and propose possible interpretations, which will be based upon the sources available to me. These sources include but not limited to: web research, existing academic literature on trench art and World War One and Two, conversations with the owners of the donated objects, discussions with Floris van Dijk and René Veldhuizen, my own cultural heritage and ability to read Russian.

Although this may have been, in part, the original goal of this research project, this paper does not make the attempt to make affirmative claims about the number of Soviet prisoners of war/forces laborers in the Netherlands, or any attempt to make empirically fixed claims about their experiences. The reason this research does not aim to do this, is because at this stage of data and knowledge we have on the subject, this is simply not feasible. As such, I encourage any reader of this inventory, to reflect and ponder together with me, about the gap that remains in our knowledge of the topic. Readers are also encouraged to think about and offer their own interpretations of the stories depicted in the collected pieces. Whilst we may have clear material evidence relating to the experiences of a certain group, we are still left with the conclusion that we know very little about them.

Key terms within this inventory:

Trench Art: This research relies on the definition of trench art as coined by Nicholas J. Saunders. Saunders focuses on trench art as a phenomenon of the 20th century, originating from the creations of soldiers during the First World War (1914-18). Naturally, Saunders reminds his readers that trench art was not unique to the First World War. Rather it is a term we can use in relation to almost any militaristic conflict. The concise conceptualization that he provides is that trench as is “any item made by soldiers, prisoners of war and civilians, from war materiel directly, or any other material, as long as it and they are associated temporally and/or spatially with armed conflict of its consequences.”[1] According to Saunders himself this definition is not perfect, perhaps too broad, and demands further investigation. The investigation into the possible types of trench art, is one of the contributions of this paper.

Saunders’ concept of trench art can be broken down into three essential elements.

- Trench art is made by soldiers, prisoners of war or civilians. It can be made by amateur artists as well as professionals.

- The materials used are not traditional canvases or artistic instruments. Instead trench art is made from materials found in the daily conditions of war.

- Trench art is created in the midst of a conflict, or after a conflict. Dealing with themes and materials reminiscent of the conflict or the socio-material consequences that followed. In the case of prisoners of war trench art, the themes of displacement and confinement are common. [2]

Saunders consciously does not narrow down trench art as a practice of a specific national identity. Rather he speaks of this as a human phenomenon. Trench art is thus a more general, human way of dealing with the horrific conditions one might face in the midst of conflict or soon after. Whilst this paper does not dispute Saunder’s argument, I will showcase how national identity still plays a very important role in the forms and symbols shown in trench art. These in turn influence our interpretations of the meanings of such works.

This paper will discuss seven pieces of trench art most made of scrap metal, some of wood, with explicit decorative elements on them. The focus will be objects made by Soviet prisoners of war, or forced laborers who found themselves in Europe and the Netherlands during the Second World War. These objects were either found at the site where the soldier was once located, within the Netherlands, or were brought to the Netherlands by Dutch soldiers.

For each piece the chapter attempts to include an accurate origin, dimensions, material and description of the piece. In analyzing each individual piece, this paper speculates on the meanings which can be ascribed to such forms of art. Was trench art a form of communication, a language in a foreign context? Can trench art be a form of asserting subjectivity and agency, even in the most dire circumstances?

Soviet prisoner(s) of war[3]: refers to Soviets captured by German forces after the German invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941. The number of Soviet soldiers and civilians captured and held in German camps during the war is generally agreed to have been around five million, of whom at least three million have been killed by maltreatment or execution.[4]

Soviet POWs mostly refers to soldiers, who were captured during combat and then generally held in specialized POW camps. If brough to Germany then POWs were often in Stalag camps. Although Soviet POWs were also documented to have been held in concentration camps such as Auschwitz, and transition camps, such as Kamp Amersfoort. POWs were often put to labor on different German infrastructural projects – building roads, defense structures (e.g. Atlantic Wall), bunkers and more. However, the functionality and forms of exploitation faced by POWs could differ a lot based on context and time of war. Generally, treatment of Soviet POWs was extremely poor, in particular due to the strong anti-communist sentiment held by the Nazi regime. For instance, we know that in Kamp Amersfoort, 100 Soviet POWs were starved and mistreated specifically for the performative purposes of an anti-communist propaganda campaign, aimed to terrify Dutch communists.

Among captured Soviets, were not just soldiers, but also civilians. Soviet civilians captured and exploited specifically for the purposes of forced labor and were known as ‘Ostarbeiters’. These individuals were also often held in prison camps. Within this inventory, we often assume that the trench art was made by POWs, soldiers, but we must be open to the fact that some pieces may have been made by Ostarbeiters. Although the distinction between the two categories may be somewhat loose, it is not unimportant.[5]

The Central Archive of the Ministry of Defense of the Russian Federation (CAMO/TSAMO) in Podolsk retains most of the existing administrative information surrounding the numbers, locations and names of Soviet POWs. [6] However, given that these archives are difficult to access without official clearing and travel to Russia, we were forced to rely predominantly on secondary accounts surrounding this history. This is noted, in order to emphasize that for the findings of this research to be more conclusive there surely needs to be further research that will be able to employ a more rigid methodology, relying on primary documentation, and more elaborate personal accounts.

In this inventory, I also make sure to consistently refer to the POWs/Ostarbeiters as ‘Soviet’. Unless a specific national reference has been made by the source. This way, I hope to avoid misleading generalizations that often occur when it comes to Soviet history by referring to all the soldiers as ‘Russian’. Being aware of the possible cultural heterogeneity of cultural backgrounds allows us to reflect on the possible plurality of meanings and messages embedded in the art, but also ensures an attempt to be nuanced in the conclusions we draw.

It is important to underscore that the state of our knowledge about Soviet POWs is somewhat limited. As mentioned above, access to Russian state archives is restricted, but even so, the documented information about Soviet POW experiences is arguably sparce for a plethora of socio-political reasons. These reasons include, but are not limited to the terrors of the Stalinist regime, Cold War tensions as well as the general post-war trauma, shame and amnesia associated with imprisonment. All of which have made the discussion of POW experiences and the collection of knowledge on the subject difficult.[7] In this context, I find it important to be a more reflexive about the goals of this research. On the one hand, the paper naturally hopes to highlight some of the previously underexplored pieces of the material evidence of the Soviet prisoner experience. On the other hand, however, the goal is not to offer fixed facts and undebatable empirics. Rather, this paper hopes to emphasize the more general, human experiences of making art and crafts in the conditions of internment and displacement in a time of war. In this instance with a focus on the Soviet cultural and social dimension of trench art.

Thank you!

This inventory would not be possible without the kind help of our colleagues and keepers of the trench art. I would like to thank Marleen Dohle for lending the piece of trench art, which she values as a family heirloom. As well as the researchers, curators and archivists who contributed to this research. Thank you Andreas Smulders of the Overloon War Museum, Eef Peeters of The Arnhem Oorlog Museum, Jory Brentjens of The Airborne Museum and Guido Abuys of Nationaal Monument Westerbork.

Thank you Floris Van Dijk and Rene Veldhuizen, of Nationaal Monument Kamp Amersfoort and Rob van der Laarse of the University of Amsterdam for your guidance and support through this research.

Object 1: ‘Tjagiev’s box’

Outline by

Outline byRené

Veldhuizen

Outline by

Outline byRené

Veldhuizen

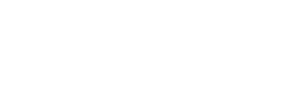

- Object number: NMKA-2020-0408

- Origin: Finding on the former grounds of Kamp Amersfoort, made in April 2020.

- Dimension (mm): 90 x 75 x 10

- Material: A soft metal, likely aluminum. Possibly a former German food kettle. Current state: surface area largely corroded and bent.

Description and reflections: The central object of this inventory, which served as the starting point for this research, is a box that we have labelled as a ‘Tjagiev’s cigarette box’. We know, almost certainly that this box belonged to one of the Soviet POWs brought to the camp in 1941, due to the information contained on the ‘back side’ of the box. The bottom edge of the back side of the box has an inscription in Cyrillic letters. The letters spell what we believe to be the name of the owner of the box, and creator of the decorative carvings. Given the rough lines and the corrosion, there may be several different readings of the letters. However, the two readings proposed in this inventory are: ‘Tjagiev A.V.’ or ‘Gjagiev A.V.’ (‘Тягиев А.В.’ or ‘Гягиев АВ.’. ).[9]

Above the name larger symbols are carved, taking up the bigger part of the box’s surface. We interpret the carvings as numbers ‘1 9 2/6’ followed by a symbol resembling a heart. Just above these symbols – is a simple triangular pattern, above which we once again see symbols resembling Cyrillic letters, in the top left corner. To me the letters above are read as the word ‘‘Год’’ – Year.

Now, to return to the front side of the box. Here we observe a carving of a smiling, feminine figure. We see the face and shoulders of a person with long hair curled at the ends in a playful manner. The chest of the person is covered in curved lines resembling something like a necklace, heavy scarf or layered clothing of a dress/shirt. The figure is placed into a ‘frame’ – a triangular pattern, just as the one from the back, is carved out along the four edges of the box, giving the drawing a sense of ‘enclosure’ and ‘completion’. Given the heart shape seen on the back side of the box, I like to interpret the woman on the front as a sentimental depiction of someone who the Soviet soldier, Tjagiev, loved. Probably his sweetheart, or a close female relative.

The sentimental power of the depiction is further increased by the likelihood that this box was probably made by Tjagiev in the camp. We cannot say for sure, but it is highly likely that whilst being held at Kamp Amersfoort Tjagiev used an aluminum food kettle to make the box, and then carved upon it. Upon closer inspection of the carving technique itself, I would describe the carvings as rather uneven, rough and probably done with a use of a blunt nail.

The depiction of a beloved woman, the carving of a name and the fact that this box was likely to have been made in captivity of the camp evokes many thoughts on the meanings and functions of this box. For instance, one way to look at this work could be as an instance of an intimate material memory. A term used by researcher Dawid Kobiałka In carrying out archeological research on the dark heritage of World War One in Poland. In his research Kobiałka discusses a metal canteen with a picture of a cuddling couple carved out by a Russian prisoner of war, at a camp in Czersk. Kobiałka argues that such examples of intimate, sentimental trench art capture the multiplicity of war camp reality. Rather than being solely representative of ‘memories of pain’ and darkness, such creations capture other emotions which might even be considered positive, such as love and perseverance but also reminiscence of the past. [10]

To conclude, the box of Tjagiev, discovered on the grounds of the former Kamp Amersfoort, is truly a precious artefact in the museums archive. Not only does it offer us several pieces of informative data, a year and name, which surely demands further expert investigation. It also invited us to ponder on the emotional and meaningful human experiences of the Soviet POWs, as well as other prisoners are Kamp Amersfoort. The box reminds us that the prisoners were not just a passive subject of Nazi violence, but also agents – carrying intimate memories along with them, which likely helped seek meaning and purpose in moments of utter despair.

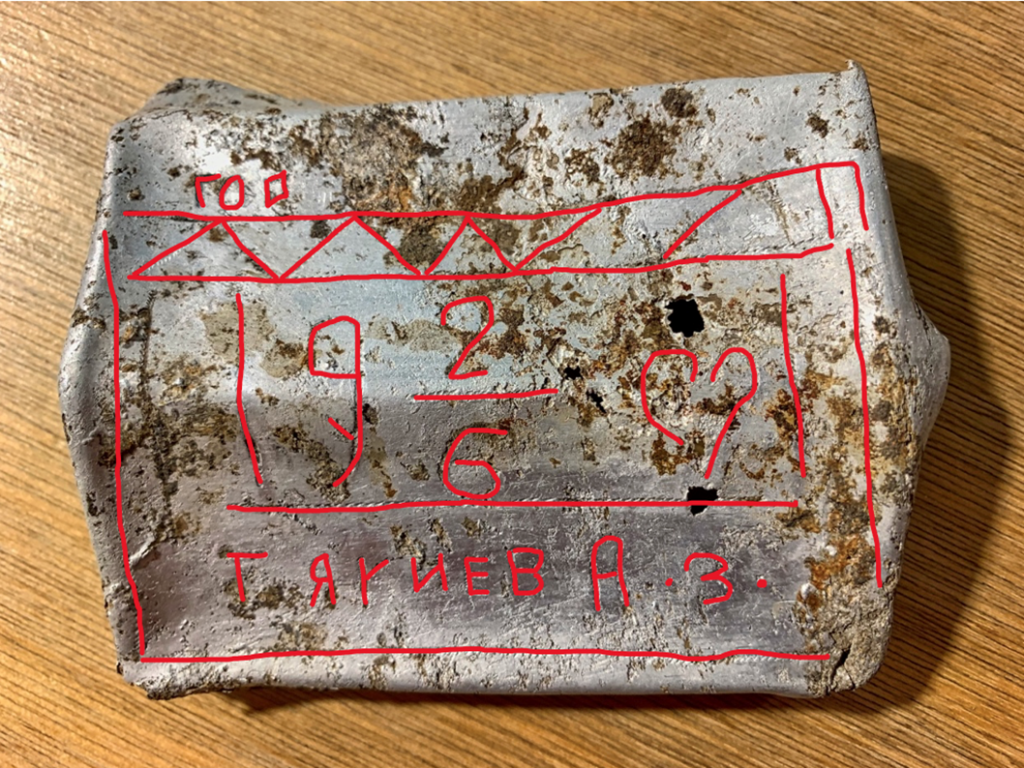

Object 2: ‘The Moscow Box’

- Object number: NMKA-2020-0227

Origin: The box was given to Nationaal Monument Kamp Amersfoort for the purpose of this research, from the collection of Overloon War Museum.

According to Andreas Smulders, the object was donated in 2009 by the family of a former Dutch soldier, C. van der Velde. Van der Velde was a POW in Stalag IV-B.[11], Mühlberg, from 1943 onwards. Given the significant number of Soviet POWs at the camp it seems probable that this box was given to Van der Velde by one of the Soviets who made the box.

Dimensions (mm): 80 x 160 x 35

Material: Aluminum

Description and Reflections: Unlike the box of Tjagiev, the box remains is in good, undamaged condition. Likely this is because Van der Velde took good care to preserve the artefact after acquiring it. Which points us to our first reflection about the story of this box. Van der Velde’s, and his family’s care for the object suggests a high level of value and importance ascribed to it. It seems probable that the box was given to Van der Velde by the Soviet POW as a gesture of comradery or possibly a valuable token in exchange something.

Although we currently cannot pinpoint the name of the creator of the box we can be almost certain that the author was probably a Russian POW, someone strongly connected to the city of Moscow. The front side of the box clearly depicts the Red Square and places Lenin’s mausoleum at the forefront of the image. The artist depicts the recognizable geometrical elements such as the unique pyramid-like mausoleum of Lenin, the triangular shapes of the Kremlin wall and the towers with stars at their peak.

It is clear that the carvings were made by a skilled individual. We see this in the almost perfectly accurate depiction of the Red Square[12], and in the techniques used to create depth and perspective. With the use of puncturing small indentations in certain areas, the artist captures shadows. The line movement from the broad right side corner of the box, into the more narrow point on the left side, create a sense of perspective. The outer edges and sides of the box are decorated with a wavy ornamental frame. Similarly to the box of Tjagiev, the ornamental frame provides a feeling of completion and structure of the carved illustration. Most lines in the image are neat and perfectly aligned, suggesting that the carver had a sharper nail or even knife to control the carving.

Whilst I believe that the carving was likely made at the Stalag, I am less confident that the box itself was handmade by the prisoner. It seems to me that the structure of the box is more rigid and complex than that of Tjagiev, and it even contains a sort of serial number on the inside (072839). Therefore, this box may have already been found or possessed by the prisoner before or during internment.

The depiction of the city center of Moscow is worth further reflection. The illustration of Moscow has both an emotional dimension, similar to that of Tjagiev’s beloved, but may also have a politically meaningful implication. To begin with the latter, I would like to highlight the choice of placing Lenin’s mausoleum at the forefront of the craving. The city center of Moscow, has historically been a politically charged space. However, the choice to depict Lenin’s tomb seems to add a specific layer of meaning – the POW is not only underscoring his identity as a (probably) Russian, and hence his allegiance with Moscow, he is choosing to highlight the mausoleum of the leader of the Russian revolution, the founder of the Soviet Union. As such, I dare to assume that this was a subtle nod in the direction of his own communist/revolutionary sentiments, which were at odds with the ideology of his Nazi captors. This is not to say that the box was necessarily a conscious expression of resistance, however, it does capture the identity of the POW as explicitly contrary to that of his captors.

In fact, research on trench art has offered several examples of similar forms of expressing a national and political identity. For instance, the research of Gilly Carr (2012) on trench art of British Channel Islanders during WWII. Carr’s study showcases how British Islanders in internment often made use of scrap from Red Cross parcels, in order to make trench art depicting symbols such as the Union Jack, the V sign and other overtly British or Churchillian symbols. Such symbols allowed for the reinstatement of national identity, and thus in Carr’s interpretation, were a form of resistance, an expression of nationalism, and support for the Allied forces. [13] As such, we know that symbolic national-political expressions are a documented phenomenon across different groups of POWs during the Second World War. Allowing us to wonder if the ‘Moscow box’ may have had a similar function. Carr’s study suggests that the British nationalist trench art was often used to express support for Allied forces, and thus performing not only the function of expressing an identity but also solidarity.[14] To me this makes the fact that the ‘Moscow box’ was given to a Dutch, fellow inmate, even more analytically intriguing. Was this perhaps a form of expressing solidarity on a more ideological level?

The potential political meaning of the box, should not, however, overshadow the emotional, sentimental, meaning that is also very likely. As suggested earlier, the accuracy of depiction, and the landscape choice, suggest that the city of Moscow contained a lot of meaning to the POW during the making of the box. This leads us to think about the theme of home, as expressed through trench art. This matter is discussed by Iris Rachamimov, in her study of POW creativity during WWI, as relating to themes of domesticity and gender. She provides several examples, especially of written art forms, such as poems and stories by POWs about their home(s). Such works often ponder on the theme of return and the change occurring at home whilst the prisoner is away. As such Rachamimov highlights how the theme of ‘home’ in POW art was an important tool in seeking hope, as well as creating a sense of temporality. Home as a reference point for both the peaceful past and the hopeful future.[15] As an example Rachamimov showcases a German POW poem titled ‘Homesickness’, the poem is accompanied by a sketch of an empty hometown street. Rachamimov, describes the sketch as: “[…] portrayed with a draughtsman’s touch an eerily empty hometown, waiting perhaps for a POW to return so it too could resume life.’’[16] I find that this description also suits the depiction of the Red Square fragment depicted on the box – calm and empty, waiting for life to return to normal.

To offer another example closer to the context of this study, we can turn to the Ostarbeiter audio archive of Memorial Society.[17] One of the interviews in the archive includes a moving story of Ostarbeiters writing songs about home. The retelling by Vadim Novgorodov talks about how during his time laboring at the mines, a fellow laborer named Oleg Frolov, wrote a song about their common home town – Taganrog. The song depicts the green landscape of Tagonrog, and the idea that the Ostarbeiters are thinking of the city as an entity, which they long for and to which they send their warm helloes to. Frolov did not survive to return to Taganrog, but Novgorodov did, and upon his return to Taganrog, added a verse to their common song. The final verse was about returning to the town, and the town remembering those who could not come back. [18]

It seems important to embed the ‘Moscow Box’ as part of a series of similar examples of trench art depicting both sentiments of home and national/political identity. I see this specific box as one of the few important pieces of material heritage, teaching us something about the broader POW experiences during the war.

The fact that the box was given to a Dutch POW, is the first example in this inventory of Soviet trench art as objects of not only individual, but social significance. Valuable items which could be exchanged in return for other goods or even as a sign of solidarity. Solidarity, allegiance and identity are also important themes which emerge when wondering about the specific choice to depict the Red Square. Was this a simple choice to depict a recognizable landscape? Or may we allow ourselves to make further interpretations about the centrality of Lenin’s mausoleum?

Finally, I personally, find the emotional dimension of depicting a home – with a specific urban focus, important. Once again, this brings us back to the central theme of this inventory – trench art as a form of ‘intimate’ memory and psychological support in dark times. We know from the research of Rachamimov and Carr that reminiscence of home through art, were common and important to POWs of all nationalities in their day to day survival. However, as shown in the archive of Memorial Society, and the ‘Moscow Box’, I find that the memory of a specific city, urban space, as a home was even more relevant in the case of Soviet prisoners. The memory and identity of a city, seems particularly more prominent in the case of a multi-national, multi-cultural state as the USSR. The entity of a city contains a more bounded and distinct set of features and symbols. For instance, the Red Square and the Taganrog seaside offer two distinctly different mnemonic and emotional signals, even though both technically belonged to a shared state and culture.

All in all, the ‘Moscow box’ is a profoundly thought provoking piece. It is unique to our inventory in that it is the only piece which contains an overtly political dimension to it and an urban landscape. Additionally, this is the first piece listed which was documented as an exchanged piece (given by a Soviet forced laborer).

Object 3: ‘The Bear and the Swan Box’

- Origin: This box was lent to the private collection of National Monument Kamp Amersfoort for the purpose of research. The box was given to us as a loan by Marleen Dohle.

Marleen Dohle received the box from her mother, Leny Grol, who lived in the village of Steenwijksmoer, Drenthe, close to the German border. During the war Leny Grol worked as a primary school teacher in a Catholic school. In Steenwijksmoer, she boarded in a house with a man, whose name Marleen does not know. Leny told Marleen that during this time, the man would ride his bike past camps near the border of Drenthe, and bring food to the Soviet POWs held in the camps. The man was given the box in exchange for the food he would bring to the POWs as a sign of gratitude. It seems most likely that he was cycling by the Emslandlager camps, probably Stalag VI C. [19] Later, the Dutch man gave the box to Marleen’s mother. - Dimensions (mm): 90 x 65 x 15

- Material: Aluminum (soft metal)

Description and Reflections: The box is a small container with a rubber button at the front side, to aid in opening. It is difficult to determine if the box was made from scratch by the internee who engraved it, or if it was a pre-existing box, only decorated by him. To me, it seems as though it was probably collected from separate boxes or restored by the creator. This is suggested by the different observable layers of the box. The bottom base, inside the box, seems to be different from the top internal side. To bottom contains cross-over lines creating a grid. The lines of the grid look perfectly measured and very smooth, as opposed to the more rigid lines that compose the image on the outside surface of the box.

Adding to the suspicion that this box was adjusted or made up from different parts of an older box, is the material at the bend connecting the two sides. Upon looking at the connecting joints of the box, from the inside, with the help of a magnifier you can see that a piece of paper with typed text on it has been folded around the joints of the box. Visible letters include the Latin letters ‘A’, ‘i’ , ‘e’, ‘n’ and ‘f’. Probably the paper came from a newspaper and was used to smoothen the opening and closing of the container.

The box contains decorative carvings on both the front and backside surfaces. The front side includes an image of a woman sitting on a lake bank and reaching out to a swan. The back, contains a drawing of a man and his companion dog, hunting a bear in the forest with a hunting rifle.

Once again, as we saw with the box of Tjagiev, and the ‘Moscow box’ the craved illustrations are surrounded by an ornamental frame. This time the frame is more distinct and plays a more important role in how the images may be read. On both sides the frame is made up of large, solid triangles alongside the edges of the box. On the backside, for the hunter image, the artist purposefully plays with the shape of the frame. As opposed to making it a traditional rectangular shape, as done on the front, the frame becomes a part of the illustration. The main frame is a 20-sided polygon, presenting a complex shape that serves as the basis for the ornamental style of the frame. The choice of using a polygon adds to the multitude of sharp angles emerging from the frame. On four sides of this shape, there are larger triangles, all facing inwards towards the image of the hunter. Altogether, this frame construction adds to the effect of sharpness and urgency of the illustrated scene. Namely, the intense moment of shooting the bear. The effect this frame creates, contrast with the more even frame surrounding the tranquil image of the woman by the lake.

It is apparent that the artist of this box, was a skilled carver. Through his technique he really built an immersive illustration, with several captivating elements. We can notice that unlike the previous boxes discussed, the illustrations here rely much more in curved lines, which add dynamic movement. For instance, the arm of the woman gently reaching out to the swan, or the pose of the hunter, leaning backwards whilst aiming his gun. We can also see layers being used to depict depth and a landscape as a backdrop to the events unfolding. The woman and swan are sitting with their backs facing a sunrise above a lake. The hunting man has a tree, hills and grass as his background.

As opposed to the first two boxes discussed, the ‘Bear and Swan’ box seems to hold a more story-telling function. Of course, the ‘Tjagiev’ and ‘Moscow’ box, give us a glimpse into a narrative about the possible experiences of the POWs. However, when comparing the three objects, I would suggest that the first two have a more ‘photographic’ function. They are aiming to capture a depiction of specific individual and location. On the other hand, here, we have a number of abstract characters interacting with each other: a woman, a swan, a man, a dog, a bear. At the same time, each character is active and embed in a natural landscape: the woman is stroking, the swan is opening its beak, the man is hunting, the dog and bear attacking. The combination of these elements with the carving technique allows us to almost imagine the movements that preceded and will follow the moment captured on the box. In turn, the box gives an effect of having a more abstract story telling function, similar to that of a graphic novel. It may be depicting events relating to the experiences of the POW who carved them, but they may also be broader, archetypical anecdotes that could appeal to, for instance, the Dutch man, who received the box as a gift.

If we are to view the illustrations on the box as a story telling devise we naturally open it up to a multitude of possible interpretations. What is this story about? The obvious, is that this is a story which has two sides. The more peaceful – woman and swan. And more active, potentially dangerous situation, of the hunting man. The interpretation which I find important to include here belongs to the current owner of the box, Marleen Dohle. Marleen grew up with the box as an important family treasure, a memory of the Second World War. The interpretation she shared with me when giving us the box was that the front depicts the peaceful times, before the war, possibly at home. The woman and the swan, are thus representation of, broadly speaking, ‘the good’. The hunting man, was seen as the representation of the war – fighting the bear, as fighting the German forces. Thus, the dark time of war.

The interpretation given by Marleen, seems most important in my opinion. This is because this box is known to us as a gift by the Soviet POW, to the man who helped him. As such, we can see the choice to depict an abstract story as a conscious choice to create a box which is not just an intimate memory to a single individual, but a shared experience, just as a story often is. Open to being looked at and re-interpreted time and time again by the beholder of the story.[20] Since the direct line of passage runs from the Soviet POW to Marleen, it is her current interpretation, through the lens of her family history, that currently matters to the box as an object of mnemonic function.

In closing, it is unfortunate, that just as with the ‘Moscow Box’, the study of the ‘Bear and Swan’ box cannot yield us certainty of its provenance or the identity of the Soviet POW who carved it. Nonetheless, this box still adds several valuable points to our understanding of the phenomenon of Soviet trench art. To begin with, this is an absolutely certain case of trench art being used as a valuable gift – not just as a currency for exchange of goods, but an actual gesture of gratitude. This teaches us of the important dynamics of comradeship and support which could emerge in times of conflict, between individuals from different states (Soviet – Dutch, in this instance). Such relationships were likely sources of hope, light and material support necessary for prisoners to survive. Furthermore, the function of gratitude expanded beyond the relationship of the Dutch man and the POW, as it later transformed into a gift to Marleen’s mother, and eventually a Dutch family treasure. Showing us the many different social functions a single piece of trench art could hold.

The box is also distinct in the carving and artistic choices that it uses. These choices are not just technically distinct to the other boxes discussed in this inventory, but actually yields a very different visual effect. Through this box, we recognize that Soviet trench art could also function as a story telling device. The story telling function, in turn, leaves itself open to an array of interpretations any one viewer may hold.

Object 4: ‘The Horse Box’

- Origin:. Stems from a private collection from Mrs. Jolanda Bos (given to us as a loan)

The box used to belong to the father of the individual who originally donated it to Nationaal Monument Westerbork. The father was a Dutch forced laborer from Zandvoort, named Henk Bos. He had brought the box from his time laboring in Germany, and it has been suggested that he received the box from a Soviet laborer working in the same region. The donator, recalls her father mentioning Crailsheim, as a possible provenance of the box.

Thanks to the digital archive research of Rene Veldhuizen, at the National Monument, we know that there was a camp in Onolzheim, a neighborhood of Crailsheim. The city archive of Crailsheim claims that this camp held between 120-300 Soviet prisoners of war, since August 1941. The POWs labored on an airbase and possibly some of Crailsheim’s factories. Little more is known about these POWs.[1] - Dimensions (mm): 62 X 70 X 17

- Material: Aluminum (soft metal)

Description and Reflections: The ‘Horse Box’ is one of the most sophisticated and detailed boxes of this inventory. It has rounded edges and an accompanying rounded lid. The whole lid and the two sides of the box are decorated with a nuanced floral pattern, which works along with the details of the box. For instance, the nails, connecting the two parts of the box, become the center for the flower (where petals connect). Given how sophisticated the structure of the box appears, I would suggest that the box itself may not necessarily have been hand crafted. Instead the POW probably made the carvings on a pre-existing box.

The centerpiece of the box, is the design on the surface of the lid. We see a detailed picture of a head of a horse with a bridle. Inarguably, the level of detail given to the face of the horse: the mane, the sharp eye, the jaw, all build up to a very realistic looking horse. Even the bridle has a small flower as a decorative detail. The horse itself is surrounded by a whirlpool of detailed patterns. The horse is circled by consecutive lines which gradually transition into lines imitating shapes of wheels (or sunshine?) on the left and right of the horse, and spirals in the four corners. The sides of the box are decorated with beautiful leaves and winding stems turning into flowers. All in all, a mesmerizing carving, and the longer you look, the more new patters appear.

Given that we have no certainty about the exact cultural background of the Soviet POW who made carved the box, I will not risk drawing rigid conclusions on the cultural significance of the horse. Nevertheless, it can be agreed upon that in many cultures horses are seen as symbols of strength, resilience, graciousness and dignity. Long term companions to humans, horses remained present in military functions during the Second World War. As such, I find it fair to conclude that together with the floral motif, the depiction of a horse was an aesthetic choice by the artist aiming to evoke many of the associated virtues of a horse. As discussed with the ‘Bear and Swan’ box, the fact that the horse has such a culturally broad symbolic appeal is particularly interesting in light of this box being given from a representative of one culture to another. Perhaps, this box, again, invites us to reflect on the unique relationship of solidarity that formed between the Dutch and Soviet people, and the abstract symbols of flora and fauna that helped communicate this solidarity through trench art.

A common element in all of the four pieces of metal trench art within this inventory has been an ornamental frame. A set of geometrical lines, patters and shapes surrounding the image. Since this particular piece is almost entirely ornamental in nature it seems worthwhile to briefly turn to some literature on the subject. Voronchikhin and Emshanova discuss the ancient roots of ornaments within different ethnic and cultural civilizations. In their definition an ornament carries out a decorative function that always combines functions of utility and aestheticizing. The authors quote Czech researcher of folk culture Josef Vydra on the four elements that define the functioning of an ornament. First, is ‘constructive’ as the ornament supports the spatial perception of the object. Second, is the ‘operational’ effect on the functional use of the object. Thirdly, ‘representational’ to increase the visual impression of the object. Fourthly, an outcome of ‘representational’ is the ‘psychic’ that works with symbolism as a way of having an emotional impact on the viewer.[22]

We could see in the earlier three boxes that an ornamental frame was used for the ‘constructive’ and ‘representational’ functions. However, within this box, we can also add the observation of the ‘psychic’. The patters have a broad floral and natural feeling to them, the curving lines, spiral, circles to me bring associations with such natural phenomena as wind, roots, sunrises.

Overall, the idea of ornaments carrying both ‘utility and aestheticizing’ functions, is echoed strongly in the nature of what trench art is more broadly. This beautiful box in particular is a great example of how trench art challenges the dichotomy between that which is utilitarian and that which is artistic.[23] Creating the box, must have carried utility in the sense of keeping the prisoner occupied, and offering a psychological form of support. Upon completion the strong aesthetic dimension further contributed to the utility of the box, when it became a valuable object to give as a gift, or token in exchange for food. As such, studying the ornamental and symbolic elements of the ‘Horse box’ reminds us that in the case of trench the functional and the aesthetic, where profoundly intertwined.

Object 5: ‘Crimea box’

- Origin: Eef Peeters from the Arnhem Oorlogsmuseum[24] sent a photo of the box and some information about it to the National Monument Kamp Amersfoort for this research.

According to the museum curator, the box came from the Rijnkade in the city of Arnhem, where a group of Ukrainian forced laborers was stationed.[25] Based on the information available to the Arnhem Oorlogsmuseum an unnamed Dutch man befriended one of the Ukrainian workers and would bring him food. The Soviet man gifted the box in return for the support. - Dimensions (mm): 108 x 80

- Material: Wood

Description and Reflections: A simple, but very pleasant handcrafted wooden box. The lid has a unique shape, the edge at the opening of the lid is carved in such a way as to create a nicely shaped nudge to help in opening the box. The surface of the lid contains three carved elements. In the top left corner we see three symbols, the letter ‘M’, ‘S’ followed by a more ambiguous symbol resembling the letter ‘t’ or some hook. At the moment, it is not possible to confidently state what these letters may be indicating – possibly initials. At the center of the lid, running from the bottom left corner to the top right corner, is the word ‘Crimea 1942’ written in Cyrillic alphabet. In the bottom right corner we see a flower.

At first glance, the carvings on the box contain some valuable points of information. For instance, the word ‘Crimea’ indicates that the maker of the box was likely Ukrainian. And if the box was indeed exchanged in the region of Arnhem, this is strong proof of Ukrainian presence there during the war. However, unfortunately at this point, it is difficult to infer more from the box, beyond some of the more theoretical points made in earlier reflections. We cannot know for certain that the box was made on Dutch soil in 1942, or if it was made earlier and brought to Arnhem. As mentioned we also cannot currently decipher the meaning of the initials M.S.t.(?).

My suggestion regarding the interpretation of the flower, is that it predominantly had a decorative function, similarly to the ‘Horse box’. We could attempt to attribute the carving of the flower to the ornamental tradition of Örnek. A long standing tradition among Crimean Tatars, depicting specific floral patterns in wood carving, embroidery, jewelry and painting. In the Örnek tradition, different types of flowers represent individuals of different ages and genders.[26] However, what makes me doubt the possibility that this is specifically Örnek, is the fact that Örnek often depicts more than one flower, or shapes, interacting with one another, building a composition which creates a story.[27] Thus, whilst there is a possibility that the maker of the box was a Crimean Tatar practicing Örnek, we can only base this on the fact that ‘Crimea’ is indicated on the box, not necessarily the carved flower. Afterall, we must remain open given that wood carving is a very common tradition amongst many different peoples of Eastern Europe.[28] All in all, this is yet another vivid case of a Soviet trench art being given to a Dutch civilian as gratitude for support. Underscoring our thesis that trench art had an important social function, mediating intercultural relationships in times of conflict. We may confidently that the indication of ‘Crimea’ was an expression of personal identity and belonging. And that the year 1942, was likely the year the box was made, potentially gifted.

Object 6: ‘Birds of Happiness’

- Origin: The Airborne Museum at Hartenstein sent a photo of the two birds and some information about them to the National Monument Kamp Amersfoort for this research.

- According to curator at the Airborne Museum, Jory Brentjens the two birds were given to local inhabitants of Oosterbeek by Georgian POWS. The Georgians were ordered to repair telephone poles. It is likely that the POWs gave these wooden birds to the local inhabitants in gratitude or in exchange for the apples and pears they received from them. According to the information available to Jory Brentjens the birds were given in the spring of 1944.

- Dimensions (mm): Unspecified (described as “small”)

- Material: Wood

Description and Reflections: Two toys of meticulous details representing birds. The body of both birds, differ slightly. But overall, in both, the body is a block of wood, smoothed down to form a curved head, neck and chest of a little bird, with a sharp edge around the top, representing a beak. Three ‘fans’[29] are attached to the body, representing two open wings and a tail. The wings and tails are beautifully comprised of wooden ‘feathers’ layered upon each other and have angular edges.

Through my Russian ‘gaze’ these birds quickly reminded me of the ‘bird of happiness’. The wooden bird, traditionally carved in Northern Russia, most popular in the city of Arkhangelsk,[30] has recognizable wings made in the same style as the birds of the Georgian POWs.

Traditional craftsman Yuri Khodiy (2011) explains that making such birds requires splitting the moist and flexible wood, for instance that of a young pine tree. This is why the bird is also known in Russian folklore as the ‘Wood chip bird’. Khodiy highlights that it is virtually impossible to make such a toy with old, dry wood.[31] Which brings about some questions about where the bird was made. Did the prisoners find the ideal wood and tools to craft the birds after being captured, or did the birds come with them from before being captured?

What is also interesting are the many symbols the bird represents. Firstly, as the name suggests, these birds are seen as symbols of happiness, due to their shape mimicking that of the sun (a rare occurrence in Northern Russia). In folklore culture the bird must hang in a family house as a guardian to bring about peace and protection from harm.[32] According to my research, this exact style of wooden bird making was not particularly prevalent in Georgian folk tradition.[33] Nevertheless, given the intertwining of Soviet cultures, it does not seem entirely unlikely that the Georgians aimed to specifically make such ‘birds of happiness’ and in doing so gifting a peace symbol to their Dutch comrades.

To close off this section, I would like to introduce an idea discussed by Yuri Khodiy, in his discussion of the craft and symbolism of the birds. Yuri ponders: Do the birds actually have the power of ward off darkness and danger? He concludes that probably not. However, he suggests that if there is any magical power to be found within the bird, it is the energy of love and care embedded into the bird by the craftsman who made it, and enjoyed the process.[34] I find that this is something to be remembered for each piece of art presented in this inventory. Perhaps, we can never accurately decipher the meanings of the symbols on each object, but we may be rather confident that each object was made with care and love for the craft. Which in itself is profoundly meaningful.

Object 7: ‘The Anonymous Box’

- Origin: This box was lent to the private collection of National Monument Kamp Amersfoort for the purpose of research by Nationaal Monument Westerbork.

- Dimensions (mm): 108 x 80 x 18

- Material: Wood

Description and Reflections: Small box with no decorative elements. Roughly cut with a lid that remains connected to the box when open. The lid contains a little extension/node in the center to aid in lifting.

Unfortunately, the lack of information or decorative elements leaves little more to be said about the box. This however, should not neglect the value of this piece as material heritage of Soviet experiences during the war.

Extra pieces: Two rings from Herinneringscentrum kamp Westerbork

The two rings presented below were given as a loan to us by Herinneringscentrum kamp Westerbork. However, the archive manager indicated that very little is known about the actual origins of the rings. The rings were donated to the memorial a number years ago – with no name, no documentation. Only statement accompanying the rings was that they are ‘Soviet’. However, the lack of any details on the provenance, and the use of Latin letters on one of the rings makes me hesitate in concluding that they are an example of Soviet trench art. Therefore, they are included in the inventory as an appendix, rather than part of the main collection.

Weight: golden ring 4 grams, silver ring 7 grams.

[1] Saunders, N., J. (2003) Trench Art, Materialities and Memories of War. London and New York: Routledge.

[2] Ibid

[3] Abbreviated to POW

[4] Lopez, L. (2025) Database of Soviet Prisoners of War Stiftung Bayerische Gedenkstätten. Available at: Database of Soviet Prisoners of War | KZ-Gedenkstätte Flossenbürg

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (n.d) The Treatment of Soviet POWs: Starvation, Disease, and Shootings, June 1941–January 1942. Available at: The Treatment of Soviet POWs: Starvation, Disease, and Shootings, June 1941–January 1942 | Holocaust Encyclopedia

Buhite, R. D. (1973) ‘Soviet‐American Relations and the Repatriation of Prisoners of War, 1945’, The Historian, 35(3), pp. 384–397. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6563.1973.tb00506.x.

[5] To further add complexity, amongst the Soviet POWs some volunteered, or were forced to serve in the German military. Soviets units within the German army were known as Osttuppen or Ostlegion. A more famous example of such a group were the Georgian Osttruppen who were stationed in the Dutch island of Texel, formally POWs the group came to serve the German Army, up until they sparked a massive revolt. However, at this moment knowledge about such legions, is not essential for the purposes of this inventory. To out knowledge, none of the pieces of trench art listed here came from a member of such Osttruppen.

[6] Keller, R., Otto, R. (1998). “Das Massensterben der sowjetischen Kriegsgefangenen und die Wehrmachtbürokratie. Unterlagen zur Registrierung der sowjetischen Kriegsgefangenen 1941-1945 in deutschen und russischen Institutionen” De Gruyter, 54(1): pp.150-180.

Additional sources on the history of and state of research on Soviet POWs will be included in the bibliography.

[7] Soleim, M., N. (2016). “Soviet Prisoners of War in Norway 1941-45- Destiny, Treatment and Forgotten Memories” Modern History of Russia. 1 pp.22-32.

[8] Porter, T., E. (2013) “Hitler’s Forgotten Genocides: The Fate of Soviet POWS” Elon Law Review, 5(2) p. 359-399

[9] Variations in how the name must be read result from the short lines and uneven ‘finishing’’ of some letters. For instance, the first letter may be a ‘T’ (T) or a ‘G’(Г) – depending on whether or not you consider the little extension of the line in the first letter as a crossbar of a T, or merely an error. Same goes for the last initial – in Cyrillic it may either be a ‘V’ (B) or a Z ‘З’. Extended notes on this matter included in my rough draft.

[10] Kobiałka, D. (2018) “100 Years Later: The Dark Heritage of the Great War at Prisoner-of-War Camp in Czersk, Poland” Institute of Archeology and Ethnology, Polish Academy of Sciences, Antiquity Publications, 92(363): 772- 787. Page:779

[11] Stalag IV-B was a large prisoners of war camp in the years of 1939 to 1945. After the invasion of the Soviet Union, many Soviet soldiers were brought into the Mühlberg (Stalag IV B) camp.

[12] On the left side of the drawing the Spasskaya (Saviour) clock tower rises. There is also a clock tower on the right, however, the addition of the clock happens to be a mistake, or an artistic exaggeration. As during the Soviet period, the Red Square only had one clock tower, whilst the rest were normal towers. To me this further supports the idea that the drawing was made from memory, within the confines of the camp.

[13] Carr, G. (2012) ‘God Save the King!’ Creative Modes of Protest, Defiance and Identity in Channel Islander Internment Camps in Germany, 1942–1945.’, in Cultural Heritage and Prisoners of War : Creativity Behind Barbed Wire. New York: Routledge, pp. 168–185.

[14] Carr (170, 2012)

[15] Rachamimov, I. (2012) ‘Camp Domesticity Shifting Gender Boundaries in WWI Internment Camps’, in Cultural Heritage and Prisoners of War : Creativity Behind Barbed Wire. New York: Routledge, pp. 291–305.

[16] Rachamimov (294,2012)

[17] Digital Archive: Та сторона, Устная история военнопленных и остарбайтеров. (The other side, Oral history of prisoners of war and Ostarbeiters). Available at: http://archive.tastorona.su/#

[18] Новгородов, В.Л. (2005) ‘Международный проект документации рабского и принудительного труда’. Available at: http://archive.tastorona.su/documents/559faa7de9be49111dd84880#. (Novgorodov, V.L. (2005) ‘International Slave and Forced Labor Documentation Project’.)

[19] Emslandlager was a series of 15 camps (1933-1945) intended for labor, punishment and prisoners of war. They were located in the moorland region of Lower Saxony, Germany. Specifically, in districts of Emsland and Benthein, with Benthein bordering Dutch provinces of Drenthe and Overijssel. Making it a reachable territory for people living in the northern part of the Netherlands and thus the likely origin of the box.

[20] Perhaps a noteworthy interpretation of the box is the choice to depict a man and a woman as symbolizing different dynamics within the story. The research of Iris Rachamimov, for instance, specifically discusses how gender roles were being interpreted and re-interpreted by German POWs in conditions of internment. Rachamimov, I. (2012) ‘Camp Domesticity Shifting Gender Boundaries in WWI Internment Camps’, in Cultural Heritage and Prisoners of War : Creativity Behind Barbed Wire. New York: Routledge, pp. 291–305.

[21] Stadtarchiv Crailsheim (no date) “Russenlager” Onolzheim. Available at: https://www.stadtarchiv-crailsheim.de/stadtgeschichte/crailsheimer-geschichtspunkte/russenlager-onolzheim/

[22] Voronchikhin, N., S., Emshanova, N., A. (2001) Ornaments. Styles. Motifs Izhevsk: Udmurtiya University. Ворончихин, Н., С., Емшанова, Н., А. (2001) Орнаменты. Стили. Мотивы Ижевск: Удмурский Университет.

[23] Carr, G. and Mytum, H. (2012) ‘The Importance of Creativity Behind Barbed Wire: Setting a Research Agenda’, in Cultural Heritage and Prisoners of War: Creativity Behind Barbed Wire. New York: Routledge, pp. 1–16.

[24] According to the museum director, the museum building itself used to house up to 400 forced laborers from Ukraine during the war. They were used for the construction of a bunker nearby. Unfortunately, beyond the memories of the mother of the museum director, it remains difficult to officially verify the information.

[25] This information currently remains unverified. I am currently unable to identify further information supporting this beyond the box itself.

[26] Chorna, K. (2019) Ornek, a Crimean Tatar ornament and knowledge about it. Available at: https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/ornek-a-crimean-tatar-ornament-and-knowledge-about-it-01601

[27] UNESCO (2019) Ornek – a Crimean Tatar ornament and knowledge about it. Available at: https://www.unesco.org/archives/multimedia/document-5626

Perhaps there is a chance that a single flower depicts a solo man? But I am hesitant to draw conclusions without deep knowledge of the ornamental tradition, as well as certainty that the maker of the box is a Crimean Tatar.

[28] When mentioning Crimean Tatars, especially in relation to the Second World War, it seems important to underscore the heavy plight of these people during this time. Crimean Tatars, have historically faced discrimination and persecution by Russian tsars. But the forceful exile of Crimean Tatars was especially egregious under Stalin, and especially during the years of the Second World War. Therefore, when we identify possible material proof of Crimean Tatar artistic practices during the war, we must be delicate and aware of the possible cultural and historiographical implications of such conclusions.

J. Otto Pohl (2000) ‘The Deportation and Fate of the Crimean Tatars’, in A Nation Exiled: The Crimean Tatars in the Russian Empire, Central Asia, and Turkey. Identity and the State: Nationalism and Sovereignity in a Changing World, Columbia University, New York: International Committe for Crimea. Available at: https://www.iccrimea.org/scholarly/jopohl.html.

[29] Resembling hand fans

[30] Scientific Library of the Northern State Medical University (2024) Library News. Available at: https://www.nsmu.ru/lib/en/about/news/bird_of_happiness_a_household_charm/#:~:text=%E2%80%9CBird%20of%20Happiness%E2%80%9D%20is%20a,11.06.2025

[31] Yuri Khodiy in ZagorodLifeTV (2011). Bird of Happiness. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KPur-_HLeyI Translated from: Юрий Ходий ZagorodLifeTV (2011). Птица счастья. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KPur-_HLeyI

[32] Ushanka Russia (2013). WOOD CHIP BIRD ( Bird of Happiness). Available at: https://web.archive.org/web/20160305102039/http://ushankarussia.com/wood-chip-bird-bird-of-happiness

[33] Although, I may be wrong.

[34] Yuri Khodiy (2011).

Cited works:

Buhite, R. D. (1973) ‘Soviet‐American Relations and the Repatriation of Prisoners of War, 1945’, The Historian, 35(3), pp. 384–397.

Carr, G. (2012) ‘God Save the King!’ Creative Modes of Protest, Defiance and Identity in Channel Islander Internment Camps in Germany, 1942–1945.’, in Cultural Heritage and Prisoners of War : Creativity Behind Barbed Wire. New York: Routledge, pp. 168–185.

Carr, G. and Mytum, H. (2012) ‘The Importance of Creativity Behind Barbed Wire: Setting a Research Agenda’, in Cultural Heritage and Prisoners of War: Creativity Behind Barbed Wire. New York: Routledge, pp. 1–16.

Chorna, K. (2019) Ornek, a Crimean Tatar ornament and knowledge about it. Available at: https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/ornek-a-crimean-tatar-ornament-and-knowledge-about-it-01601

J. Otto Pohl (2000) ‘The Deportation and Fate of the Crimean Tatars’, in A Nation Exiled: The Crimean Tatars in the Russian Empire, Central Asia, and Turkey. Identity and the State: Nationalism and Sovereignity in a Changing World, Columbia University, New York: International Committe for Crimea. Available at: https://www.iccrimea.org/scholarly/jopohl.html.

Keller, R., Otto, R. (1998). “Das Massensterben der sowjetischen Kriegsgefangenen und die Wehrmachtbürokratie. Unterlagen zur Registrierung der sowjetischen Kriegsgefangenen 1941-1945 in deutschen und russischen Institutionen” De Gruyter, 54(1): pp.150-180.

Kobiałka, D. (2018) “100 Years Later: The Dark Heritage of the Great War at Prisoner-of-War Camp in Czersk, Poland” Institute of Archeology and Ethnology, Polish Academy of Sciences, Antiquity Publications, 92(363): 772- 787.

Kobiałka, D. (2019) “Trench art between memory and oblivion: a report from Poland (and Syria)”, in Journal of Conflict Archeology, 14(1): 4-24.

Rachamimov, I. (2012) ‘‘Camp Domesticity Shifting Gender Boundaries in WWI Internment Camps’’, in Cultural Heritage and Prisoners of War : Creativity Behind Barbed Wire. New York: Routledge, pp. 291–305.

Saunders, N., J. (2003) Trench Art, Materialities and Memories of War. London and New York: Routledge.

Stadtarchiv Crailsheim (no date) “Russenlager” Onolzheim. Available at: https://www.stadtarchiv-crailsheim.de/stadtgeschichte/crailsheimer-geschichtspunkte/russenlager-onolzheim/

UNESCO (2019) Ornek – a Crimean Tatar ornament and knowledge about it. Available at: https://www.unesco.org/archives/multimedia/document-5626

Ushanka Russia (2013). WOOD CHIP BIRD ( Bird of Happiness). Available at: https://web.archive.org/web/20160305102039/http://ushankarussia.com/wood-chip-bird-bird-of-happiness

Sources in Russian:

Digital Archive: The other side (n.d.) Oral history of prisoners of war and Ostarbeiters. Available at: http://archive.tastorona.su/#

Translated from original: Та сторона (n.d) Устная история военнопленных и остарбайтеров. http://archive.tastorona.su/#

Novgorodov, V.L. (2005) ‘International Slave and Forced Labor Documentation Project’. Available at: http://archive.tastorona.su/documents/559faa7de9be49111dd84880#.

Translated from original: Новгородов, В.Л. (2005) ‘Международный проект документации рабского и принудительного труда’. Available at: http://archive.tastorona.su/documents/559faa7de9be49111dd84880#.

Voronchikhin, N., S., Emshanova, N., A. (2001) Ornaments. Styles. Motifs Izhevsk: Udmurtiya University.

Translated from original: Ворончихин, Н., С., Емшанова, Н., А. (2001) Орнаменты. Стили. Мотивы Ижевск: Удмурский Университет.

Yuri Khodiy in ZagorodLifeTV (2011). Bird of Happiness. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KPur-_HLeyI

Translated from original: Юрий Ходий ZagorodLifeTV (2011). Птица счастья. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KPur-_HLeyI

Extra sources on Soviet POWs and Ostarbeiters:

Much of my understanding about the history of Soviet POWs and Ostarbeiters comes from the many works of the historians listed below, as well as the research by International Memorial Society. I am sure there are historians I am unfortunately missing in this list, but hope that a curious reader will find it valuable to turn to at least some of these scholars for further details on the story of Soviet POWs in Europe.

Berkhoff, K., C. (2001). “The “Russian” Prisoner of War in Nazi-Ruled Ukraine as Victims of Genocidal Massacre”, Holocaust and Genocide Studies, 15(1):1-32.

Bernstein, S. (2018). “Ambiguous Homecoming: Retribution, Exploitation and Social Tensions During Repatriation to the USSR, 1944-1946” Past and Present Society, no.242 p. 193-226.

Otto, R. (2011) ‘Cemeteries of Soviet Prisoners of War in Norway’, Historisk tidsskrift, 90(4), pp. 531–557.

Otto, R., Keller, R. (2018). “Soviet Prisoners of War in SS Concentration Camps: Current Knowledge and Research Desiderata”. In: Kay, A., J., Stahel, D. et al. Mass Violence in Nazi-Occupied Europe, 123,-141. Bloomington, Indiana University Press.

Polian, P. (2005). “First Victims of the Holocaust Soviet-Jewish Prisoners of War in German Captivity” Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History. 6(4): pp.763-787.

Porter, T., E. (2013) “Hitler’s Forgotten Genocides: The Fate of Soviet POWS” Elon Law Review, 5(2) p. 359-399.

Soleim, M., N. (2016). “Soviet Prisoners of War in Norway 1941-45- Destiny, Treatment and Forgotten Memories” Modern History of Russia. 1 pp.22-32.

True-Biletski, K., Redert, P. (2016). “ ‘Russenlager’ and forced labour. Soviet prisoners of war in Bremen – ‘home’ as a reference for historical memory. Creating an exhibition on a voluntary basis: a case study” Museum and Society, 14(2) pp.382-396.

Zemskov, V., N. (1995). “Repatriation of Soviet Citizens and their fate (1944-1956)” Sociological Research, 5, 3-13